Vanilla is a variety of orchid, and as such, is a fickle bitch. There, I said it, orchids are assholes. There is no other explanation as to why a plant would thrive on a particular kind of neglect that actually requires a lot of effort. Vanilla orchids, in particular, are the mysterious lovely plant that gives us the vanilla bean. That sweet, wonderful smell simultaneously takes us to a tropical island and our grandmothers’ kitchens. This delightful flavoring is in almost every baking recipe.

But it almost wasn’t.

Vanilla, much like its tasty counterpart chocolate, comes to us from the Aztecs. In 1519 the Spanish conquest brought both back to Europe to the delight of the white rich and powerful. Live plants were brought back in the hopes of cultivating vanilla beans for the larger European market. Sadly, none of the flowers ever produced a vanilla bean. But the Europeans kept trying their gosh darn hardest.

Literally, hundreds of years passed. In 1836 Belgian horticulturist Charles Morren proposed that vanilla wouldn’t grow as it lacked its natural pollinator, the Melipona bee, which does not live in Europe. As it turns out, the Melipona is probably not the natural pollinator, and there is still debate on what is. But he was correct in his summation that the flowers weren't being pollinated. And in 1839, he wrote to hand fertilize the vanilla orchid, "It is thus necessary to raise the velamen or cut it when the plant is to be fecundated and to place in direct contact the pollen and the stigmatic surface."

Problem solved, right? Wrong. With no other context given, no one had any idea what he was talking about.

Being the capitalist-driven idiots that rich white Europeans were, they decided, “Hey, you know what would be a good idea? Growing a fuck-ton of that plant, no one has ever successfully pollinated and sell the beans no one has ever grown. But it’s cool, we will just grow them in a climate similar to Mexico’s, and it will be fine.” And thus, French colonists of the 1820s planted a host of vanilla orchids on Madagascar's islands in the hopes of creating a vanilla empire.

It was not fine.

Edmond Albius crica 1863 with vanilla orchid growing up a tree.

Enter Edmond Albius. In 1841 Albius was a 12-year-old slave owned by Ferreol Bellier-Bauemont. Bellier-Beaumont had a vanilla bean plantation on the island of Réunion for 22 years. And in that time, do you know how many beans he had? Zero. That's right. The plants that never fruited continued to never fruit. Shocking, I know.

That is until one morning in 1841, Bellier-Beaumont was walking with Edmond when they came across the last surviving vanilla plant; only two discover not one but two vanilla beans! Bellier-Beaumont was shook. But not as shook as he was when Albius told him that he, a 12-year-old African slave, had succeeded where hundreds of years of white men had failed.

Edmond had previously learned how to hand pollinate watermelons by “marrying the male and female parts together.” After learning this basis of horticultural production, Albius spent the next few months studying the orchid until he was able to identify the two parts of the orchid that must touch for pollination to happen.

Bellier-Beaumont, still somewhat skeptical of Edmond, asked him to do it again. Albius did. And the flowers that he hand-pollinated continued to produce. Bellier-Beaumont sent Edmond from plantation to plantation, having him teach the technique to all the other slaves.

And thus, a failing industry of white men was saved by the brilliance of a 12-year-old black slave.

You would think that due to the service he provided and the multi-billion-dollar industry he single-handedly created; Edmond Albius was rewarded. But sadly, this is not the case.

Bellier-Beaumont gave Albius his freedom and wrote to the governor asking that Albius be paid “for his role in making the vanilla industry.” But nothing came of it.

Left destitute, Edmond turned to a life of crime to support himself and was eventually sentenced to five years in jail. Once again, Bellier-Beaumont wrote to the governor stating:

I appeal to your compassion in the case of a young black boy condemned to hard labor … If anyone has a right to clemency and to recognition for his achievements, then it is Edmond … It is entirely due to him that this country owes [sic] a new branch of industry—for it is he who first discovered how to manually fertilize the vanilla plant.

This time the governor responded and had Albius released. But still without any hope of financial compensation.

Then French botanist Jean Michel Claud Richard, claimed that he had invented the method to pollinate vanilla orchids. He claimed to have traveled to Réunion in 1838 to teach the technique, and somehow Edmond must have seen him perform the technique.

Bellier-Beaumont denied these claims and defended his former slave, pointing out all the inaccuracies in Richard's story, including the fact that there were literally no vanilla beans grown in captivity before Edmond, and no one remembered Richard being on the island or teaching the technique:

I have been [Richard’s] friend for many years, and regret anything which causes him pain, but I also have my obligations to Edmond. Through old age, faulty memory, or some other cause, M. Richard now imagines that he himself discovered the secret of how to pollinate vanilla, and imagines that he taught the technique to the person who discovered it! Let us leave him to his fantasies.

Despite some effort from Bellier-Beaumount, and his truly remarkable innovation, Edmond lived a poor difficult life and died in 1880 at age 51. His obituary in the Moniteur reads, “The very man who at great profit to his colony, discovered how to pollinate vanilla flowers has died in the hospital at Sainte-Suzanne. It was a destitute and miserable end” (August 26th, 1880).

Recipe

Homemade Vanilla Extract:

Homemade vanilla extract is straightforward to make. All it takes is plain-tasting alcohol, vanilla beans, a sealed jar, and time. Vodka is the typical choice for vanilla. Despite the name "bourbon vanilla," bourbon does not refer to the alcohol-infused, but refers to the Isle of Bourbon, the former name of the Réunion, where the vanilla industry was born. That being said, don’t feel constrained with using vodka. You are the master of your own destiny. You want to use bourbon in your extract, use bourbon! You want rum? Great! Brandy, why the fuck not? Do whatever makes you happy.

Supplies:

1 8oz sealed jar *

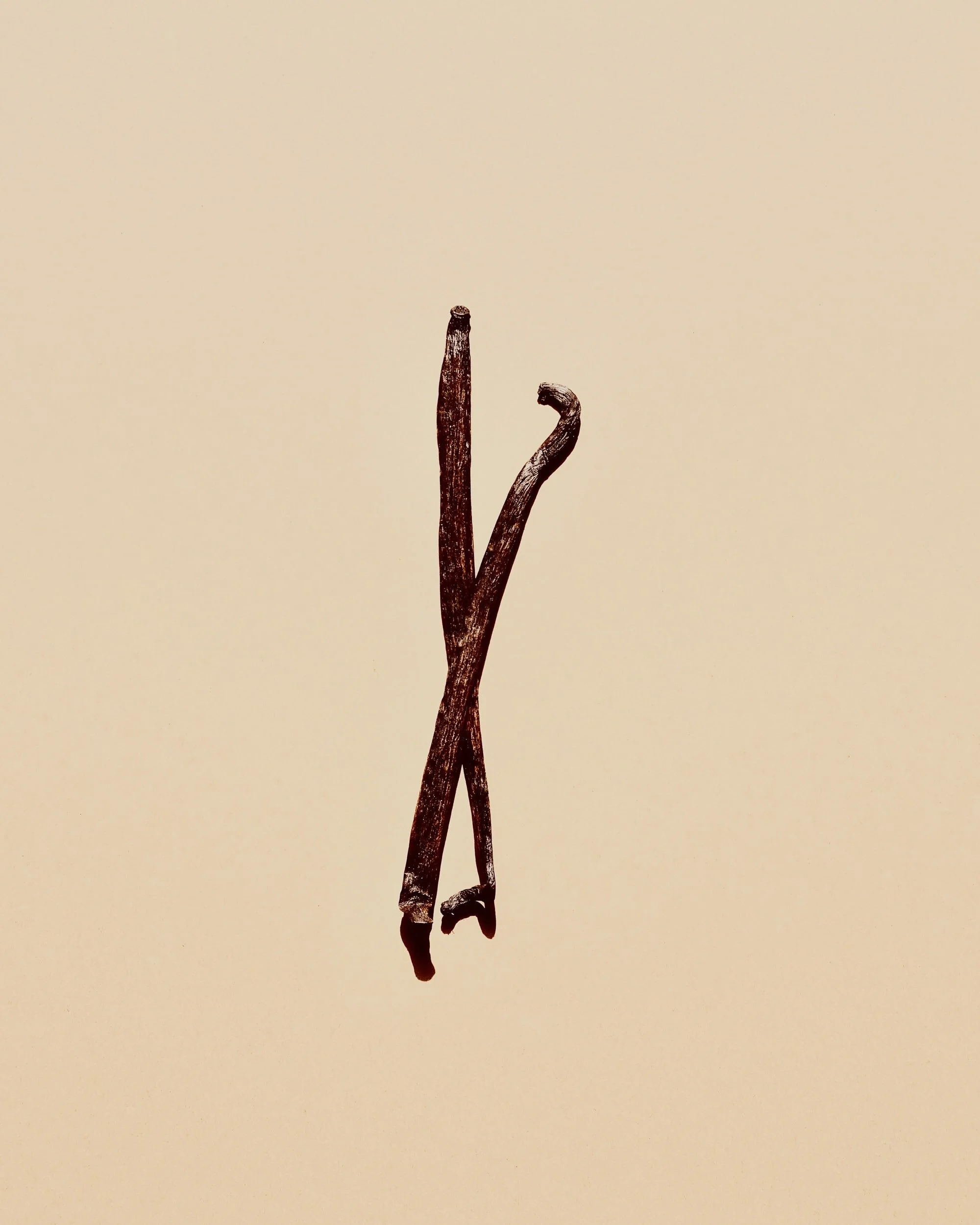

4-6 vanilla beans**

1 cup alcohol

1 funnel, recommended

Instructions:

Cut vanilla beans in half and split open.

Place at least 4 whole beans (8 halves, or up to 12 halves) into the container.

If using, place your funnel in the mouth of the container. Fill the jar with 8oz alcohol of choice.

Seal your jar and place it in a dark place to rest.

Forget about it. Forget about it for at least 8 weeks. Maybe shake it once in a while. It is okay to leave it longer. Real pure vanilla extract literally never goes bad. And unlike spices, the longer it sits, the more potent it gets. Found an old bottle from 7 years ago in the back of your pantry (not that I’ve done that…)? Go ahead and use it! Make a bunch of these and let them sit for 10 months until the holidays. Your family will love you.

*I used a repurposed whiskey flask

** Yes, it is a lot of beans. Get thee to a Costco!