Why Witches Look the Way They Do

Fall is here, which means it’s time for all things creepy, kooky, mysterious, and spooky!

I have always loved this time of year. As a kid, it was the best because you got to dress up in costumes and eat way too much candy. As an adult, it remains the best because you get to dress up in costumes, eat way too much candy, AND drink fantastic beer!*

It is a truly magical time.

With that in mind, we are going to talk about the secret history of witches and beer.

This post has to do with witch imagery in Anglo culture, starting in about the 15th century, the modern representations of witches in that culture, and their intrinsic tie to medieval beer brewing. Other parts of the world also have fascinating histories of powerful, mystical women that you can read about here, here, and here (among other places.)

Now, then…

In medieval England, beer brewing was initially done in the house and was seen as one of many domestic tasks for which women were solely responsible. During the late medieval evil period, women began to share the brewing, making large batches of ale and selling it.

Then in the tail end of the 14th century, following the first round of The Black Death, the world began to change. Grain became cheaper, people began living closer together in urban settings, quality of life increased. With these changes came an increase in beer brewing ability and the rise of the alehouse. And the people of medieval England sure did drink. Some estimates are up to a gallon of ale per person per day.

While, yeah, that is a lot, it isn’t quite as bad as it sounds. There were practical reasons why medieval Brits drank so much ale.

Beer also provided many vital nutrients, including carbs, to help keep people working throughout the day. At the time beer was also less alcoholic than today’s brews, coming in at closer to 3% alcohol. While this meant you didn’t get as much of a buzz and it didn’t last as long, The fermentation process also killed bacteria that lived in the water. Not a bad thing when you are working your way in and out of plague outbreaks…

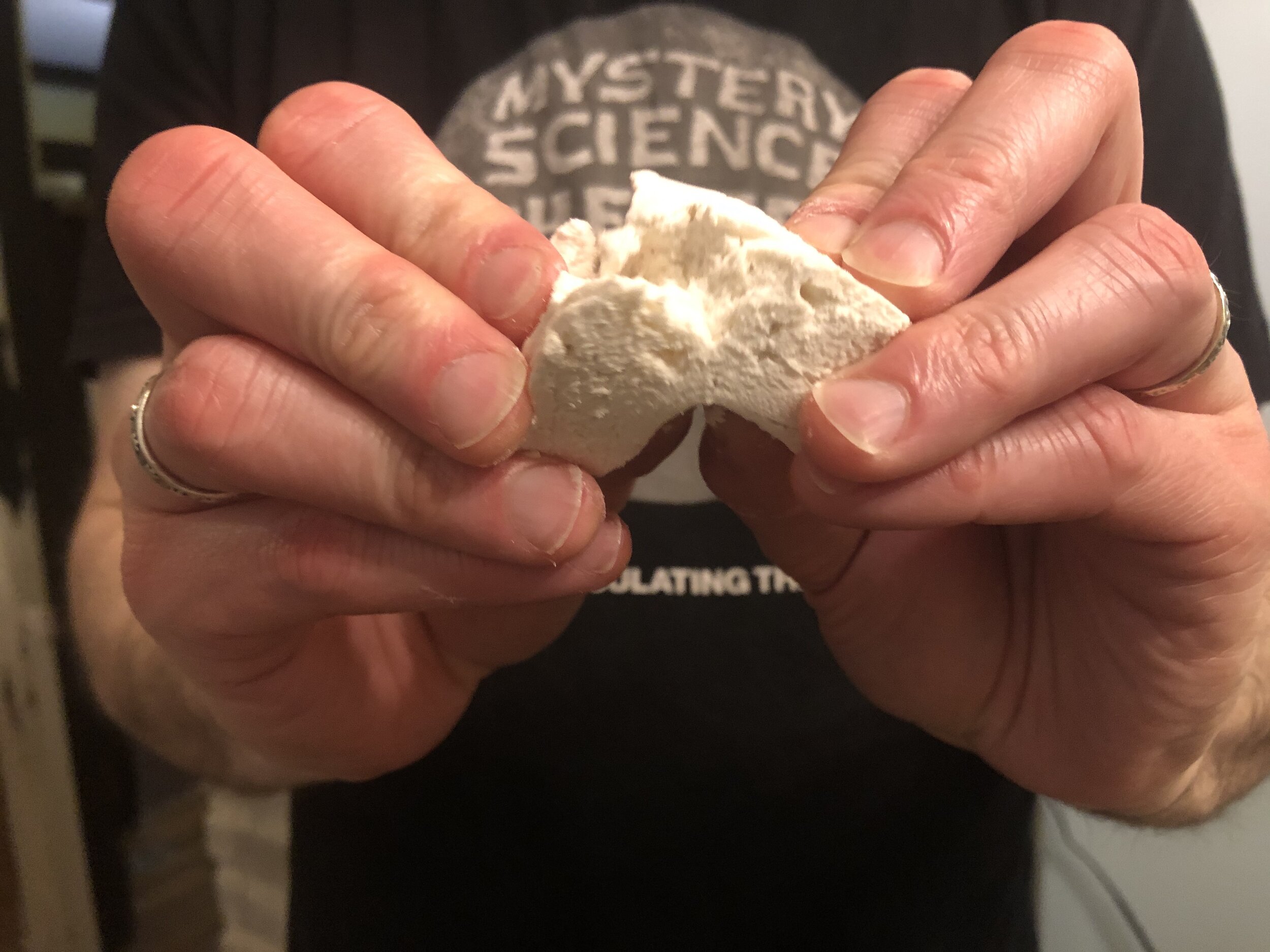

While there were male brewers, the profession particularly appealed to women. Brewing and selling beer (a trade known as tippling or tapping) allowed women to work in a well-paid profession. Medieval England had a lot of restrictions on what professional work women were and were not allowed to do. Brewing provided many with enough income that they could support themselves. By 1400 the women who worked in these professions began to be known as Alewives.

Ale Wife

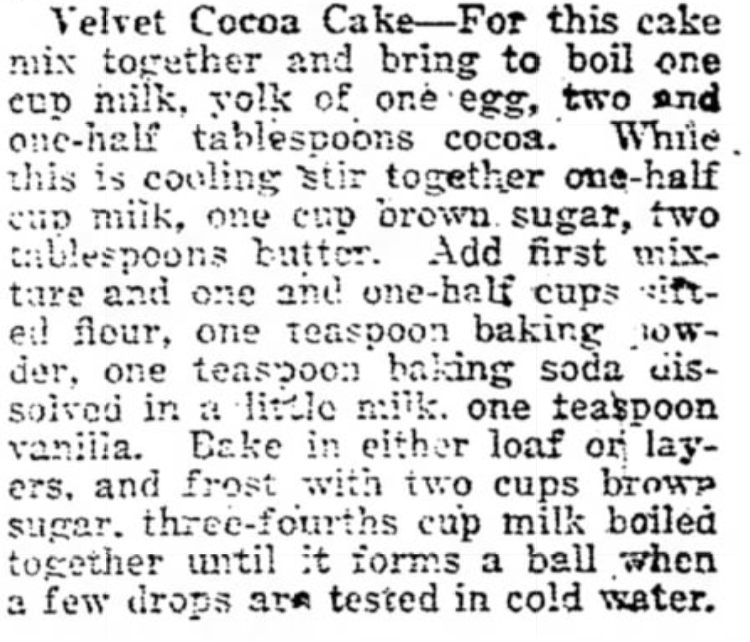

Witch costume from Amazon.com

You may notice some similarities between the above picture and our imagery of witches.

Hats: Alewives and tipplers wore tall hats, sometimes pointed, sometimes flat. The reason was simple: marketing. It marked alewives for their profession and made it easier to find the barkeep and order the next pint of ale. This style of hat also went on to become incredibly popular. Hennin hats were wildly trendy by the 14th and 15th centuries, and in the 16th and 17th capotain and Phrygian hats became popular. Both look remarkably similar to those depicted on witches. In fairness, there were a lot of tall hats being worn at the time.

“Witches hat”

Cats: This one is pretty simple. Cats eat mice. Mice eat grain. You can’t make beer without grain. It was not uncommon for brewers to keep cats around to keep the mice at bay and protect their grain. Over the centuries, many pets have been linked to accused witches as “familiars” but the cat remains the most popular image.

Caldrons: To make a batch of beer, you have to make a large pot of wort. In the 15th century and until reasonably recently, large pots of anything were made in heavy cauldrons set over a fire.

Brooms: To signal a batch of ale was complete, alewives would hang an alestake or ale pole out the window. Depending on what source you look at, the alestake was either a typical broom to symbolize domestic work or a branch with a bush or garland attached to the end. Either way, it doesn't take a lot of imagination to understand how that simply became a “broom” after hundreds of years.

Ale pole signaling ale is ready

Alewives had a pretty good deal, especially for being women in a horribly patriarchal society with limited knowledge of personal hygiene. But then, greedy men had to come and ruin it. The powerful men were unhappy that these women had found a way to make a life and name for themselves outside of their society's strict confines.

The Church was unhappy that women began to hold jobs—jobs that provided alcohol. Depictions of alewives started to take on sinister imagery with horns and nakedness. Between the Church and government, rumors spread of alewives as thieves and tricksters, swindling men out of their money, deceiving their clients. At the same time, male only brewing guilds were formed. Men began opening taverns of their own. Despite being men being just as deceptive in business as women, only women got a bad reputation.

As time went on, many alewives were accused of witchcraft and persecuted. Unfortunately, there was a grain (pun intended) of truth to this that allowed the hysteria to take hold. A fungus called Ergot was common on barley grain. It was so common that it was assumed the black kernels that replaced portions of the grain were just part of the plant. However, Ergot is hallucinogenic, similar to LSD. But as Sarah Loman put, it "only gives you a bad trip." This could account for the idea of flying specters and men claiming to have been “enchanted” by women.

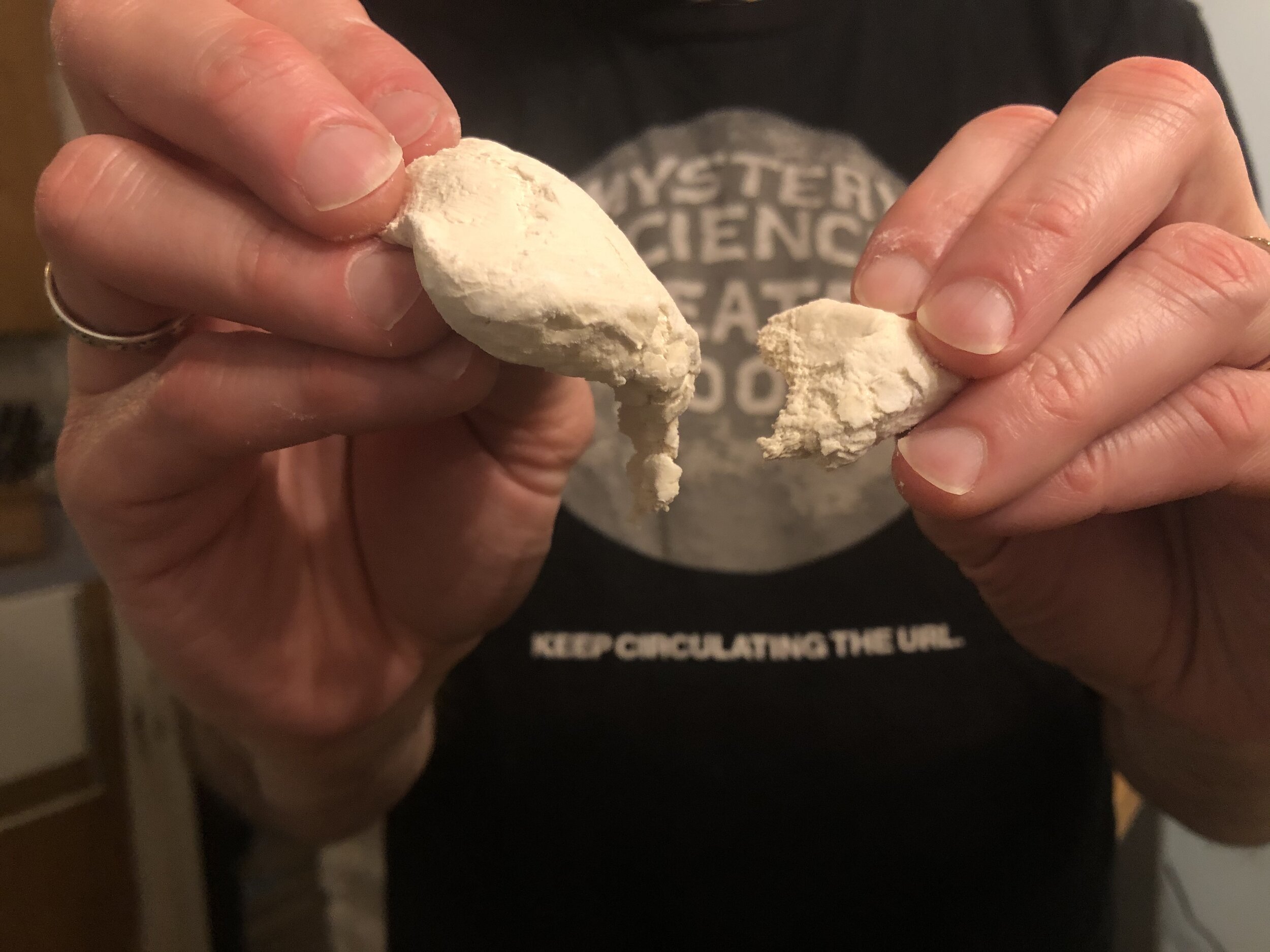

Ergot infested rye

Women continued to brew beer despite being literally murdered for it. (But what weren’t they going to be murdered for? Honestly.) Still, by the 1600s, men had become the primary brewers, and the image that once represented an alewife became synonymous with evil witches.

There is still debate among historians on whether witches' eventual imagery is the direct result of the Church's smear campaign on alewives, or nearly coincidence. To me, the evidence is overwhelming. And one thing is sure, the modern-day witch certainly does look like the strong brewing witches of old.

Happy haunting, everybody!

Recipe

1 bottle of beer

Chilled drinking glass or mug

Instructions:

1. Pour beer into a chilled glass or mug

2. Drink

Follow me on Instagram and Facebook for more great recipes like this one.

*In fairness, I don’t really like beer but I love October, and I’ve been assured that there is a lot of good beer to be had during Octoberfest…or at least that after long enough no one cares.